MacKINTOSH, Charles Rennie

As Charles Rennie McIntosh, he was born at 70 Parson Street, Glasgow on 7 June 1868, the fourth of the eleven children of William McIntosh (c.1837–1908), a clerk in the Glasgow police force, and his first wife, Margaret née Rennie (c.1837–1885), his father changed their name to MacKintosh in 1892. MacKintosh was educated at Reid's Public School and Allan Glen's Institution, both in Glasgow 1875-1884, then an articled pupil in the office of local architect, John Hutchison 1884-1889, followed by work as a draughtsman with Honeyman & Keppie of Glasgow, where he remained for most of his architectural career. While training as an architect, Mackintosh also attended Glasgow School of Art 1883-1894, working closely with sisters Margaret and Frances MacDonald (1873-1921), painting complex watercolours, and designing posters and works of decorative art. In 1896 a competition was held for the design of a new building for Glasgow School of Art, to be built in the centre of the city and Honeyman & Keppie won the competition with a design by Mackintosh. In 1897 he designed stencilled decorations for Miss Cranston's, Buchanan Street tea-rooms and in 1898 furniture for her Argyle Street tea-rooms. It was work such as this which first brought Mackintosh to the notice of the public, his architectural work was done in the name of Honeyman and Keppie but in 1897 the 'The Studio' art magazine published two articles by Gleeson White on Mackintosh and his designs. On 22 August 1900 Mackintosh married at the episcopal church at Dumbarton, Margaret Macdonald and moved to an apartment at 120 Mains Street in the centre of Glasgow, the interior of which was of their designs. In late 1900, Mackintosh and his wife travelled to Vienna to supervise the installation of their work at the eighth exhibition of the Wiener Sezession, the leading avant-garde art group in the city. After suffering from alcoholism, when his friend and mentor Francis Newbery, head of Glasgow School of Art, suggested that he and his wife might benefit from a creative break in the Suffolk town of Walberswick. Just after the Mackintoshes arrived for their summer break the First World War broke out, and a decision was made to stay in Walberswick for a full year. Mackintosh was no stranger to the area, having spent shorter periods of time in Norfolk and Suffolk in 1897 and 1905, surviving drawings from the 1897 visit include detailed studies of Blythburgh church. Soon after his arrival in Walberswick, Mackintosh's condition began to improve and he set to work on some detailed topographical drawings and watercolours, near the river. He also made a careful study of Bell Cottage, now almost unchanged after well over 100 years, these drawings are all dated 1914 and were dated from the early part of his stay. Owing to the First World War, tight restrictions were soon introduced concerning access to militarily sensitive areas, and artists working 'en plein air' were regarded with great suspicion and by the end of 1914 trouble was brewing for Macintosh. His earlier connections with the Viennese Secession and close friendship with architect Hermann Muthesius (1861-1927) were no secret, and his inclination to go for evening walks with a forbidden lantern led to rumours that he was a spy, signalling to foes at sea. He was arrested after just under a year in the village ‘on suspicion' and held in what was effectively house arrest at Westwood Cottage, where the painter Arthur Dacres Rendall had a studio. Metal worker Philip Frederick Alexander of Millfield Road, Walberswick negotiated his release, but not before he had been banished from the three East Anglian counties for the duration of the war. In August 1915 they found two studios to rent in Glebe Place, Chelsea where they spent the next eight years with little money and little prospect of work in a city during wartime. Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke (1877-1953), a manufacturer of scale models and an ardent modernist, asked Mackintosh to remodel a small house for him at 78 Derngate, Northampton and Mackintosh's vivid, Viennese-inspired interiors show that he had regained his creative nerve. The watercolour still-life's that he painted at this time and the textile designs which he and MacDonald produced in their hundreds were sold to manufacturers to make ends meet. In 1923 Mackintosh and his wife went to the south of France, initially for a holiday staying in the Roussillon region often in Port Vendres, a busy small town where the cargo boats unloaded from Algeria. Mackintosh now painted with a steady purpose, producing a series of more than forty watercolours, views of rocks, buildings, and landscapes. These later watercolours were much more ambitious than most of those he had painted in Glasgow or Walberswick. In May 1927, his wife returned to London for six weeks for medical treatment and Mackintosh wrote to her every day and in one of the letters he wrote that his tongue felt swollen, which turned out to be cancer of the tongue. Becoming seriously ill, in the autumn of 1927 he was taken back to London and, after treatment at Westminster Hospital, was unable to speak. Charles Rennie MacKintosh died at 26 Porchester Square on 10 December 1928. The standard account of Mackintosh's life and work is Thomas Howarth's 'Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement' (1952)

Works by This Artist

|

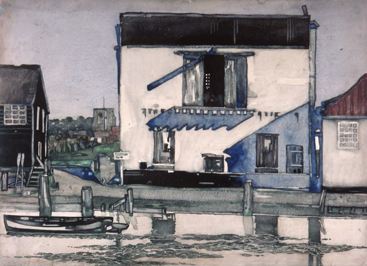

Venetian Palace, Blackshore on the Blyth, SuffolkWatercolour

|

|

Chickory, WalberswickWatercolour and pencil

|

|

Ivy Seed, Walberswick 1915Pencil and watercolour

|

|

A Hill Town in Southern FranceWatercolour

|